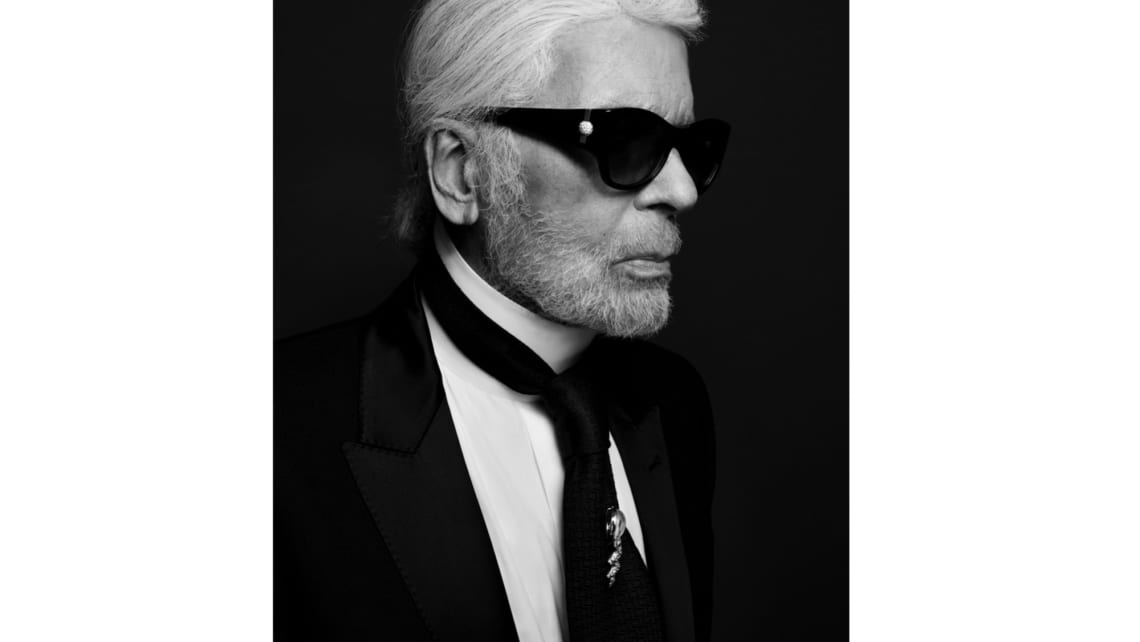

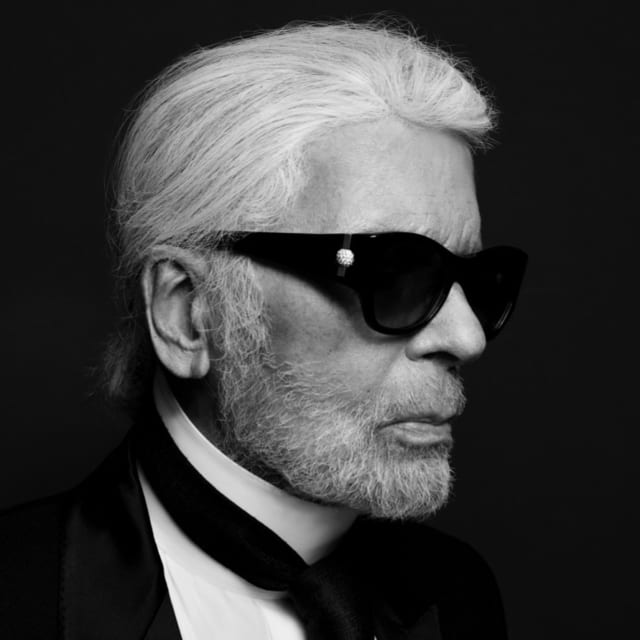

Karl Lagerfeld, designer of Chanel and Fendi, passed away today, February 19th, in Paris at the age of 85. Here, Roger Tredre looks back at the designer’s decades-long career and legacy.

The death of Karl Lagerfeld at the age of 85 is a seismic happening in the fashion world. When the designer missed his own Chanel haute couture show in January, whisperings about his ailing health circulated. But in the end his death still came as a surprise – the way Lagerfeld, a man who enjoyed keeping people guessing, would probably have liked it.

No designer remained as influential for as long as Lagerfeld, with the exception of Coco Chanel, whose mantle he inherited. Right up until his death, long after most of his contemporaries (including his long-time rival Yves Saint Laurent) had retired from the fray, Lagerfeld was still acknowledged as a vibrant, inspirational force and integral to the continuing allure of the house of Chanel.

That said, Lagerfeld the designer was always something of an enigma. His skill in updating other fashion houses’ signature styles tended to overshadow his own personal style. Lagerfeld, a line launched in the 1980s that bore his own name, never drew the plaudits of his work for Chanel, Chloé or Fendi. He was, perhaps, the ultimate, flexible, modern, mercenary designer, able to adapt, transform, modernise and amaze – a chameleon without equal who created the template for so much in contemporary fashion, inspired and prompted by a series of muses and alliances, such as his friendship with the Italian fashion editor Anna Piaggi. He tended to eschew fashion theorising, making what he described as ‘just great clothes, no great theories behind it’. But behind the oft flippant and frivolous exterior was a designer who worked fanatically hard and treated fashion with deep seriousness. In the twilight of his career, Lagerfeld retained the capacity to surprise and delight, his designs for Chanel full of the joie d’esprit of a much younger man. His capacity for hard work was legendary, although even his most fervent supporters recognised that he had over-reached himself in 1993, when he was simultaneously designing for Chanel, Fendi, Chloé and his own Karl Lagerfeld lines. The signature lines that bore his name had a chequered history; the core line, Karl Lagerfeld, folded in 1997 but was relaunched and had a number of investors over the years including Tommy Hilfiger Group, Apax Partners and PVH.

His determination to remain ever-relevant to a new young generation was palpable, reinforced by his dramatic weight loss in 2001 (94 pounds in thirteen months), which made a statement to the world that he was an ageless designer with plenty yet to deliver. Likewise, when he auctioned off his collection of eighteenth-century art and furniture at Christie’s in 2000, he made it clear that he was resolutely looking to the future. Even a questionable decision to produce a signature capsule collection for mass-market fashion retailer Hennes & Mauritz in 2004 was a defiant statement of youthfulness.

Despite his deep understanding of history, Karl Lagerfeld showed little respect for it. His mantra was ‘modern’, a word repeated in countless interviews over the decades. Since his appointment as head of design at Chanel in 1982, he simultaneously trashed and cherished the Chanel heritage. The appointment initially shocked the Paris fashion milieu – Lagerfeld was considered a styliste rather than a couturier, and he was a German outsider. But his skills, usually (although not always) applied with a lightness of touch and wit, made him synonymous with the modern house of Chanel. ‘Only the minute and the future are interesting in fashion – it exists to be destroyed,’ he said. ‘If everybody did everything with respect, you’d go nowhere.’ The Wertheimer family, who control the privately owned label, made it clear that he had a job for life, releasing financial figures only once (in June 2018) to reveal that Chanel is a business with revenues of $10 billion.

Lagerfeld worked at a feverish pace, producing a flood of detailed sketches, a veritable torrent of creativity. A Lagerfeld collection, for whichever label, was marked by clear ideas expressed with confidence and assurance, often with a high degree of wit. His debut for Chanel in 1983 was a triumph, the star piece a trompe l’oeil silk crepe dress featuring jewellery-effect embroidery by Lesage, a playful reference to Madame Chanel’s delight in jewellery. For inspiration, his first Chanel collection looked back primarily to the 1920s and 1930s rather than to Chanel’s post-war comeback. His extravagant use of Chanel’s interlocking C motifs was there from the start. While there were always some ready to dismiss Lagerfeld’s style as baroque showmanship sharing more in common with Chanel’s arch-rival Elsa Schiaparelli, by the end of the 1980s few could seriously challenge Lagerfeld’s position at the top of the fashion pyramid, particularly with Yves Saint Laurent close to retirement.

Over the years, Lagerfeld’s designs for Chanel drew from all periods of the fashion house’s history, often with unexpected juxtapositions, such as denim jeans mixed with a classic soft tweed jacket or a heavy leather biker jacket with a silk tulle ball gown. Lagerfeld’s design aesthetic was always brasher than the original Chanel – whether reflected in an intense colour palette for tweeds or in flashy luxury bags and other accessories or in a constant willingness to appropriate street style. But Lagerfeld’s oft strident aesthetic reflected a more strident age. ‘I took her code, her language and mixed it all up,’ he said in 2004. Humour was one of the most potent weapons in the Lagerfeld armoury. Anna Piaggi, a fashion eccentric of the first order, was drawn to Lagerfeld by his playful eclecticism: the first Lagerfeld-designed dress in her wardrobe was in silk embroidered with sequins with a motif of an Art Deco pop jukebox.

Lagerfeld grew up accustomed to money and luxury and never experienced the financial hardships of many of his contemporaries. He was born Karl Otto Lagerfeldt in Hamburg, Germany, the son of a Swedish business magnate who had made a substantial fortune in the condensed milk industry. He claimed a birth date of 1938, although baptismal records suggest he was delivered five years earlier in 1933. His German mother, Elizabeth, was a formative influence on the young designer, a demanding personality who shaped her son to develop a similar iron will and continued to be an important force in his life until her death at the age of 81 in 1978. He moved with his mother to Paris in 1953, making his big breakthrough two years later when he won an International Wool Secretariat award for a coat. The young Yves Saint Laurent won the dress award, setting the stage for two careers that marched in parallel through the 1960s, 1970s and beyond. Lagerfeld’s path to glory was, however, much slower than Saint Laurent’s. The coat award in 1955 enabled Lagerfeld to land his first job at Pierre Balmain, from where he moved to Jean Patou after three years. But he was quickly bored and left within a year in a significant shift from the world of couture to ready-to-wear, freelancing for names ranging from Krizia, Charles Jourdan and Mario Valentino to supermarket chain Monoprix. He was avowedly a styliste – the French word for a designer who worked for ready-to-wear labels. That put him, in the eyes of the oft snobbish world of French fashion, at a considerably lower level than the couturier Yves Saint Laurent. Lagerfeld’s response was to celebrate his role as styliste, deriding the craft of haute couture as old-fashioned and backward-looking. The fierce professional rivalry turned deeply personal in the 1970s when Saint Laurent had an affair with Jacques de Bascher, the long-term amour of Lagerfeld.

Ever restless, Lagerfeld was briefly disillusioned by the world of fashion design for a period in the early 1960s and moved to Italy in 1964 to study art. Within three years, however, he was back in fashion at the house of Fendi, forming a bond with the Fendi family that has lasted even longer than the Chanel connection. From 1964, he also worked fruitfully with the ready-to-wear house of Chloé under the guidance of founder Gaby Aghion, who taught him how to edit and simplify the flood of designs he was producing. In the 1970s, his work for Chloé established him as one of international fashion’s leading designers. The 1972 Deco collection, featuring black-and-white prints and inspired bias-cut dresses, received universal acclaim. For ten years, as chief designer at Chloé, he produced a stream of collections that summed up the fashion spirit of the period, leading to his appointment at Chanel in 1982. He briefly returned to Chloé in 1993, although less successfully.

Lagerfeld’s talents extended beyond fashion design into photography and illustration – and no doubt he would have been his own best biographer. Speaking to Roger Tredre in 1994, though, he said he would never write his story for a simple reason – ‘I could not write the truth.’ Author Alicia Drake was brave enough to exhaustively research Lagerfeld’s rivalry with Yves Saint Laurent in the 1970s in her book, The Beautiful Fall: Lagerfeld, Saint Laurent, and Glorious Excess in 1970s Paris (2006). Lagerfeld felt wounded by the book, taking legal action which resulted in its withdrawal in France by publishers Bloomsbury.

Restless and easily bored, Lagerfeld was the German outsider who became the ultimate insider in the gossipy world of Parisian fashion. He was a media dream, accessible and obliging, enthusiastically ready with a pithy quote and a pleasure in stirring up mischief. His wide-ranging interests and exceptional gift for languages made him a one-man publicity machine for whichever label he is representing. He had a sense of theatre (indeed, he has designed costumes for theatre, opera and cinema), invariably arriving fashionably late for appointments, usually in a flurry of energy and impatience, borne with equanimity by his colleagues in the Chanel atelier. His showmanship and extraordinary speed of work were both depicted admirably in the French television documentary, Signé Chanel, first screened in 2005. He was admired (and sometimes mocked) as a fashion spectacle in his own right. In the 1950s, Lagerfeld used to drive a cream open-top Mercedes, a present from his father, and wear high heels and carry clutch bags on holiday in Saint-Tropez. Fifty years on, his spectacular diet was partly linked to his desire to squeeze into the slim-line tailoring of Hedi Slimane, the young designer at Dior Homme whose work he has championed. He often expressed a cultural affinity with the cultivated aristocrats of eighteenth-century Europe, even half-jesting that in a previous life he was an eighteenth-century gentleman. Since 2012, his treasured cat, Choupette, achieved celebrity in her own right with her own Twitter and Instagram accounts and line of beauty products.

During the first two decades of the twenty-first century, Chanel’s presentations became ever-more lavish, with high-spend sets for shows staged in the Grand Palais in Paris or at sumputuous locations around the world. For autumn/winter 2014 ready-to-wear, he mixed up familiar tweed suiting with trackpants and sneakers, all wittily presented in a Chanel ‘supermarket’ (the shopping baskets were made of Chanel chains). Less successful was the feminist edge to the spring/summer 2015 collection featuring a mock demo for women’s rights: while it tapped the mood of the times, left-leaning critics accused Chanel of jumping on a bandwagon. From 2002, Lagerfeld staged an annual Chanel Métiers d’Art show, technically a pre-fall collection, presented in a different location worldwide every year. The event, which usually prompted a media frenzy wherever it popped up, highlighted the craftsmanship of Chanel and the specialist ateliers it worked with, such as Lesage for embroidery, Lognon for pleating, and Lemarié for its signature feathery camellias. The show presented in New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art in December 2018 managed to blend Ancient Egyptian and modern Manhattan street style. In the same month, Chanel showed it was moving with the times by banning the use of exotic skins and furs.

Despite his long career and open engagement with the media, Karl Lagerfeld remained a mystery, the real man behind the fast-talking ‘Kaiser’ tending to be obscured from view by the media persona. His predilection for dark glasses or the protective carapace of a fan suggested that this was the way he preferred it. Perhaps the truth was not so complicated – his life was his work. Certainly, that appeared to be the reality after the death of his long-time close friend Jacques de Bascher in 1989. On the subject of work, Lagerfeld said: ‘You have to remember that I do nothing else. That’s how I manage. Twenty-four hours a day. I don’t go on holiday.’

Lagerfeld’s offence at Alicia Drake’s exploration of his rivalry with Saint Laurent in the 1970s was clearly deep. Drake sought to delve deep into the Lagerfeld psyche, soliciting comments from a wide variety of sources. She explored his many personal rivalries and his recurring tendency to fall out with even the closest of friends, ranging from Gaby Aghion at Chloé to the model Inès de la Fressange. On his obsession with youth, Drake quoted an anonymous former colleague: ‘If you want to understand Karl, you have to understand his fear of death . . . He talks about the future non-stop because when he looks at the past he realises that life is behind him and there is only a small portion ahead. This is what makes him work so hard.’

As a designer, he consistently set new standards for productivity and energy, driving fashion forward into the modern age. He also created a template that was followed by Tom Ford at Gucci and a host of designers in the 2010s, showing how fashion and fashion labels can be endlessly revived and made relevant for every new generation.