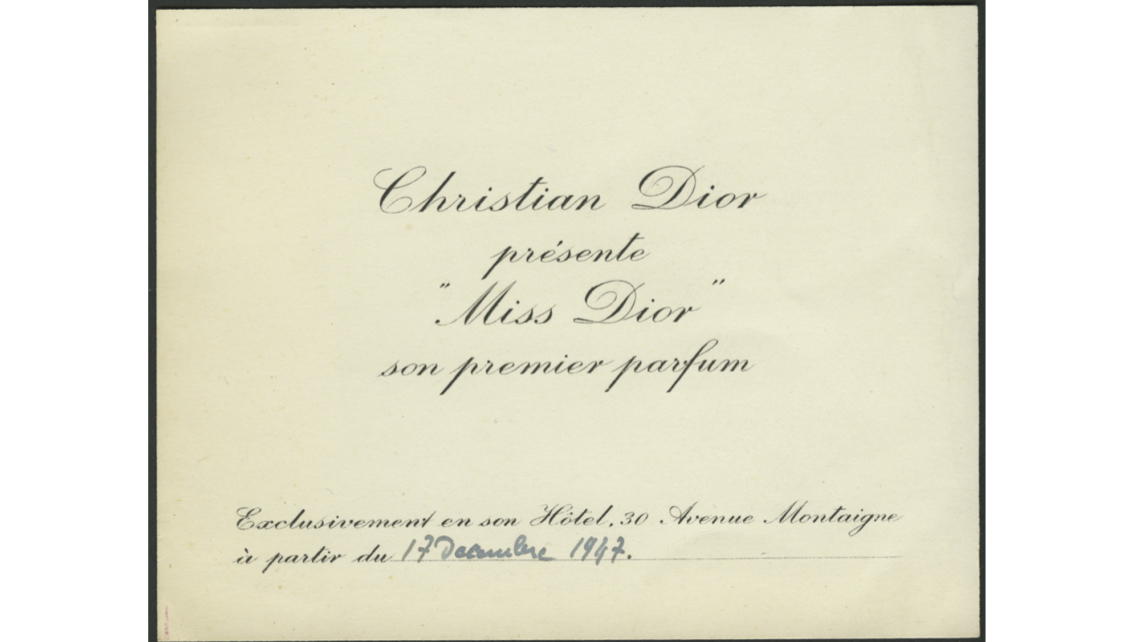

In his 1951 autobiography, Christian Dior wrote: “What I remember the most about the women who were part of my childhood was their perfume; perfume lasts much longer than the moment.” Guests at the launch in 1947 of his first perfume, Miss Dior, never forgot the olfactory aspect of the occasion as assistants sprayed more than a liter of the scent around the showroom.

As anyone reasonably well-versed in fashion history knows, Miss Dior was named in honour of the couturier’s younger sister, Catherine. On hearing his muse and advisor Mitzah Bricard greet Catherine Dior’s arrival at her brother’s studio with the words “Voilà, Miss Dior!”, Monsieur Dior was apparently heard to remark: “Miss Dior… Now there’s a name for my perfume.” A year before her June 2008 death, Catherine Dior confirmed the story at a French Resistance memorial service.

Although fiercely proud and defensive of her brother Christian and his legacy, Catherine Dior was not what you might describe as a fashion person. Nor, on the other hand, was she by any means conventional. As well as being a highly decorated French Resistance veteran and a survivor of the Nazi gulag, she was one of the few women ever granted a government license to act as a Mandataire en fleurs coupées or “cut-flowers broker.”

This hard-earned status accorded Caro––as her family and friends called her––the right to trade internationally in cut flowers from France and its colonies. From the late 1940s throughout the 1950s, Caro was a familiar sight at the Les Halles market in central Paris, often arriving at 4 a.m. with her companion and former Resistance comrade Hervé Papillault des Charbonneries to begin brokering deals with florists around the world.

Market people who remembered Caro from this time spoke not only of her drive but also of her utmost honesty and probity, a rarely accorded compliment in French business circles at the best of times, especially in the case of women daring to penetrate the glass ceiling that still covers France to this day. Caro also dealt in flowers grown on her property Les Naÿsses in Callian, a few miles to the west of Grasse, where Parisian perfume houses have sourced the flowers for their scents over the past few centuries.

Caro inherited her love of flowers from her mother, Madelaine, remembered for her management of the gardens at the family home, Villa Les Rhumbs, in Normandy. The Dior family came from Granville, a fairly posh resort town on the western Norman seaboard at the foot of the Cherbourg peninsula where the English Channel meets the Atlantic Ocean. Caro’s father, Maurice, was a successful fertilizer producer and the family was wealthy. By the time Catherine was born in 1917, the Diors had moved to Paris but had kept Les Rhumbs as their family seat and so, Caro was born in Granville.

Widowed in 1931, Maurice Dior then suffered financial ruin as a consequence of the 1929 Crash and moved the family to the South of France where property was cheaper and he was able to buy Les Naÿsses. As for Villa Les Rhumbs, the town of Granville purchased the clifftop villa and its grounds in the 1930s, intending to demolish it. Fortunately, the property was turned into a public park instead and in the 1990s was transformed into the Musée Christian Dior, with Catherine Dior as its Honorary President until her death in 2008.

As soon as Caro was old enough, she would visit her brother Christian in Paris. By 1937, Christian Dior was working for the avant-garde couturier Robert Piguet alongside other future luminaries like Pierre Balmain and Marc Bohan. This interlude ended when Christian Dior was called up after the declaration of war in September 1939. He had previously completed his year of military service in 1927 and 1928 with the Fifth Engineer Regiment in Versailles, conveniently close to Paris.

Fortunately for him, Christian Dior’s unit was not in the path of the German advance in May and June 1940 and he and his comrades were demobilized relatively soon after the Franco-German armistice on June 22nd, 1940 instead of being sent off to prisoner of war camps in Germany for two or three years. Dior did not return to Paris until the end of 1941 but stayed in the Unoccupied Zone of France where he often stayed at the family home in Callian.