“I want to be able to represent them all, but it will take a couple of lives. One continent, 54 countries,” says Timbuktu-born Malian designer Alphadi. “Every African has a different story to tell.”

Reflections on Africa Fashion

These words reassured me about the V&A’s approach to its much-touted Africa Fashion exhibition, which runs until April 2023.

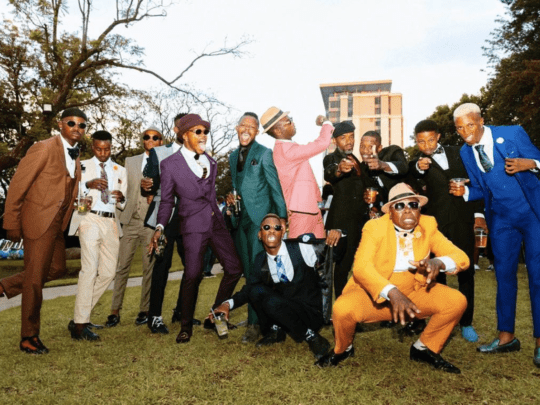

Image Courtesy of the V&A Museum

I had my reservations about how a Western institution such as London’s V&A might try to narrate the histories of African fashion. I’m a “Born-Free” Black, Xhosa South African, from a country with 11 other tribes that each have their own histories, dialects and ways of sharing and preserving knowledge and culture. I’ve seen what happens when you try to homogenise these cultures into one big “Rainbow” quilt – it’s not very convincing.

Full credit, then, to the curatorial team and lead curator Dr Christine Checinska. I had feared the V&A might retroactively attempt to right, and rewrite, the pervasive wrongs of Britain’s history. I had also feared the clumsy use of broad-stroke storytelling. But a text at the beginning of the exhibition served as a disclaimer – and perhaps a challenge by the curatorial team to the museum – positioning the exhibition as a starting point rather than a final statement.

I agree. Now the V&A has set the stage (and challenge) for itself to progress to telling stories about Africa that are regionally and culturally nuanced – in the same way that it might explore the French Revolution or the Rococo period in European art history.

I have consistently seen Africa written from outside of it, according to the myth and exotification of the Western gaze. I have digested outdated textbook definitions of ideas and movements authored by Western voices. There’s a lingering refusal to process African art as art, rather than artefact, bound up in curiosity cabinets. We’re represented through the unchanging, “othered” lens of the “primitive”, lodged in the past.

Image Courtesy of the V&A Museum

But let’s turn to the detail of the exhibition. Draped head to toe in Rich Mnisi, the dancers of Lakin Ogunbanwo’s “Who Dey Shake” were the first details I saw of Africa Fashion, projected onto the domed ceiling of the V&A. I felt a tinge of excitement.

Africa Fashion articulates well the key role of fashion as an archive in itself; the ultimate time-keeper and a vehicle for memory, cultural inscription and communicating renewed identity, and political belonging. Dress and textiles have long illustrated selfhood and the things that people hold near and dear, such as education and a sense of national rebirth and pride in moments of independence and revolution. Where Africa’s academics, intellectuals and political leaders took on the risk of communicating with their words, dress – cloth, in particular – communicated those concerns on a vernacular level.

There’s a comment that resonates: “Cloth is to Africans what monuments are to Westerners.” Cloth is a consistent and ever-evolving presence – from adaptive traditional dress practices to the Nelson Mandela-embellished Kanga cloth that an auntie might wrap around her waist. It has shown up throughout the 20th and 21st centuries as a conduit of African contemporaneities, introducing new forms of national dress that test the boundaries of tribalism. Through cloth, African communities complicate the story a little, foregrounding innovation and lateral, cross-cultural/trans-national exchange (by the way, the absence of Shweshwe, a printed, dyed cotton fabric widely used in southern Africa, was a missed opportunity).

Image Courtesy of the V&A Museum

Dr Christine Checinska and the curatorial team of the exhibition sought to narrate an African continent that has a complex, cosmopolitan history in which African people and cultures have migrated and informed one another for centuries. The exhibition illustrated a narrative of trans-national cultural exchange by touching on the landscapes of music and print media, which embodied the sense of optimism that underpinned the era of independence on the continent. It explored the idea of African fashion existing beyond the colonised national borders and divisions of East, West, North and South, an approach that resonated with me.

Some key words in the exhibition catalogue: “Even in a bold and colourful dress, there is also the quiet of a coming together. That possibility that we, all of us, can know one another.”

There’s something emancipatory about the possibility of saying no to the colonial borders that have thrown our varied communities into the chaos of tribalism and xenophobia. Twentieth century designers Shade Thomas-Fam, Chris Seydou, Naima Bennis and Alphadi were among the key names chosen to reflect the diverse and global influences of African designers.

Image Courtesy of the V&A Museum

There could have been much more on the vast and varied East African fashion histories, as British-Somali Diamond Abdulrahim, who joined me at the exhibition, noted. “I recognise it’s a near impossible feat to capture the richness and variety of the African continent in any field, let alone fashion but it’s unfortunate that even within the paradigm of Africa certain geographical regions are privileged over others,” she says.

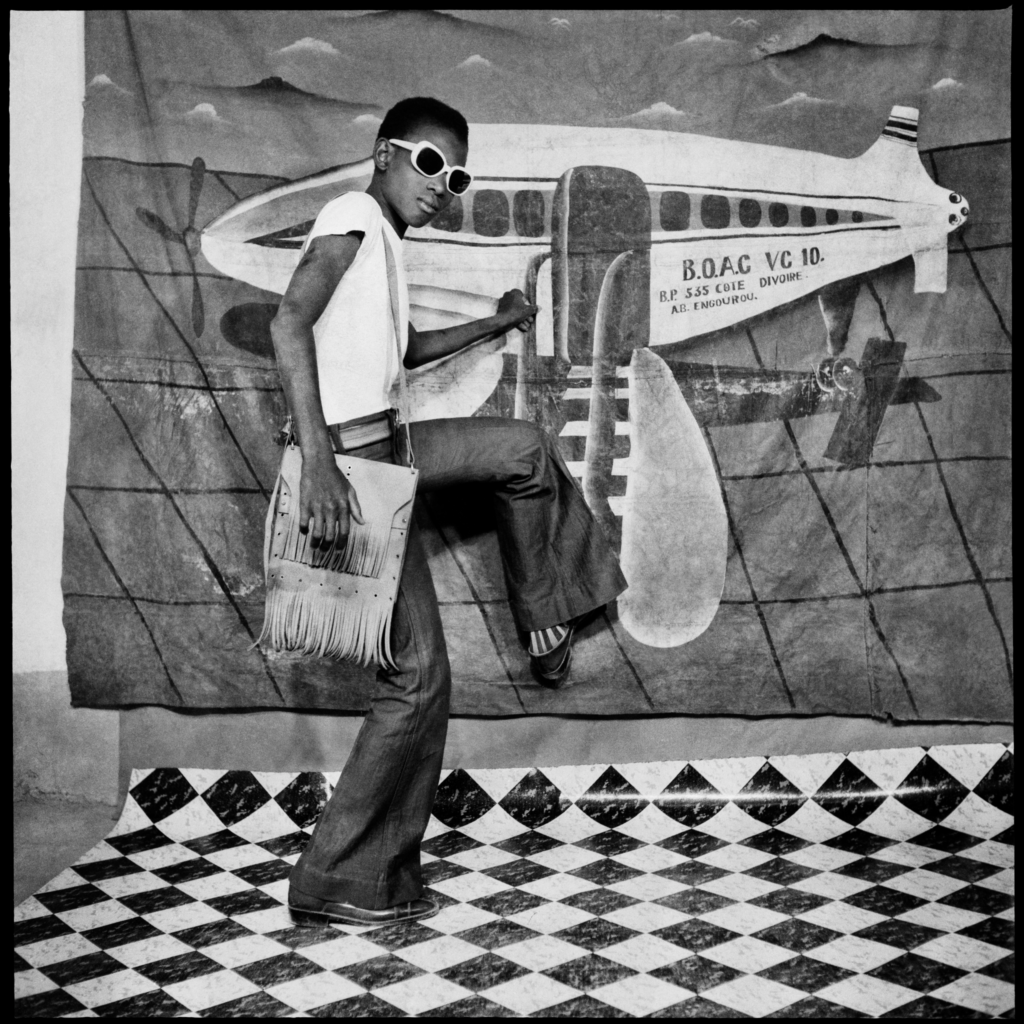

The recurring theme of self-authorship shifts in form, communicated in the exhibition through clothing, jewellery, the body and the photograph. Though the photography section favours West African stories, it felt nostalgic and familiar, reminding me of my own parents’ and grandparents’ photo albums, and their relationship with the camera as a documentary instrument. Conversations that I have had with my family around photography seem to open doors for an almost romantic remembrance of difficult times. My mother once explained to me the enfranchisement, status and personal economic progress that owning a camera tokenised for herself and her parents. Through self-produced/home-made fashion photographs, individuals turned the lens on themselves, imagining themselves as jet setters.

The notions of “cool” that they asserted are well-represented in the African diaspora’s western fashion histories, but tell the story of an entirely different relationship with fashion in Africa during the post-independence era. The bold showing off that one could do in the cosseted space of the photo studio could make you a target in public. It was a means of speaking and writing when either one could land you in detention. I was reminded of old photographs of my uncles in front of their cars and workplaces; making a show out of adjusting the volume on a radio, just to show their technological savvy; in their church uniform holding hymn books. My mother, a township pageant princess in her teenaged years, permed and producing high-flash recreations of a model’s headshot.

Image Courtesy of the V&A Museum

In the final section of the exhibition, the dancing models I had glimpsed at the beginning were now bigger and closer, their braids and twists swift and mobile as they bounced and posed for their hidden friend behind the camera. John Cena rapper Sho Madjozi’s interpretation of the Xibelani (a traditional XiTsonga skirt) stood alongside the elaborate, patterned two-piece Tokyo James suit worn by Nigerian singer Burna Boy. Here, we were firmly positioned in the present of fashion in Africa, where artists and celebrities model creativity and luxury, just as in the rest of the world.

It was a grand, swelling conclusion. I was taken aback by how much I was reminded of home; the bright lights of a bustling and ever-expanding Sandton. I thought of my peers and the multiple, yet somehow balanced co-existence of African identities that continues to confuse many, including our parents’ generation. The unending creativity, hustle and space-making that takes place within this organised chaos.

Image Courtesy of the V&A Museum

Familiar names came up; I felt the warmth of recognition when I saw my tribe represented in MaXhosa Africa’s modern interpretations of IsiXhosa traditional colours and patterns; the familiar divination mat onto which designer Thebe Magugu threw bones and turned his ancestors’ message into a two-piece garment in his AW 2021 collection, titled Alchemy. Lukhanyo Mdingi, whose work consolidates a history of craftsmanship with modern design, has continued his exploration of collective movements and creative labour in fashion. The ensemble from his Perennial AW 2019 collection pays homage to the history of South Africa’s mohair trade.

Minimalist forms – so rarely read as synonymous with African creativity – were represented by Rwandan designer Moses Turahirwa’s Spring/Summer 2018 collection titled Intsinzi, with an elegant pale blue top and pants as a contemporary take on traditional Rwandan dress. No form is as unifying and broadly familiar to Africans from each corner of the continent as the iconic checkered plastic Mas’goduke bag, otherwise known as the “Shangaan Bag” or “Ghana Must Go”, which made an appearance in Nkwo Onwuka’s Nkwo.

The African continent is just that – a continent. No story covering 54 countries can do them justice, but common threads were established. If Africa Fashion is a starting point – as it declares itself to be – then I am intrigued by what comes next in African storytelling at the V&A.

Image Courtesy of the V&A Museum