Confidence is the most valuable thing money can buy. For a lucky minority, it comes with education if you grow up in a comfortably-off family and have the fortune to be privately educated.

Look forward in anger

But that confidence is difficult to replicate if you haven’t grown up in such an environment, especially when it comes to navigating the elite spaces of the fashion industry. Imposter syndrome is a common feeling among students studying fashion.

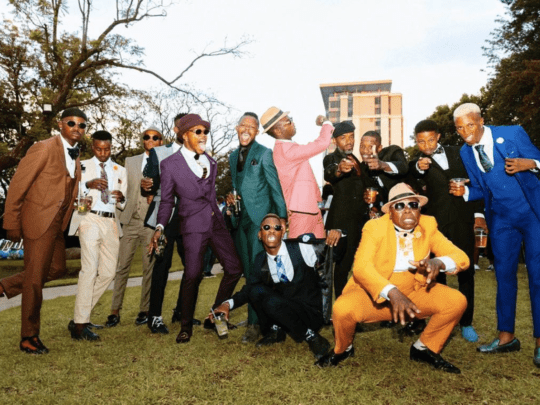

Image courtesy of Osman Yousefzada

And then there’s the challenge of explaining your hopes for a career in the fashion industry to your father – in my case, an ex-coal miner whose understanding of fashion doesn’t extend beyond the pair of 30-year-old Levi’s in his wardrobe.

Growing up in a working-class family, luxury fashion always seemed so glamorous and out of reach. Then, abruptly, fashion changed tack and it became ‘cool’ to emulate your DHL delivery man (see Vetements, 2015) rather than the glitz usually associated with high fashion. For many fashion obsessives nowadays, it’s about replicating a ‘poor chic’ aesthetic, albeit at designer prices. Think Balenciaga Paris high-tops.

The appropriation of a working-class ‘aesthetic’ is nothing new to the fashion industry. References to working-class lives have regularly popped up on the runway. Back in the 1960s, a wave of working-class photographers and models swept into Swinging Sixties London and challenged a posh industry to respond to real lives rather than a pampered few. In design terms, the working wardrobe has been appropriated and carved up by any number of designers over the decades. Consider the year 2018, when Prada featured ID badges as accessories in its Autumn/Winter collection, while Calvin Klein, then designed by Raf Simons, made use of a faux fireman aesthetic.

Image courtesy of Osman Yousefzada

An obsession with workwear and the service industry is an appeal to the everyday through appropriating uniforms. Consider how Demna’s SS 2018 collection for Vetements features the stereotypes of delivery man, tourist, security guard and pizza delivery boy. Heart-felt? I’m not sure: to me, it came over as a mockery of the service industry, portraying workers as caricatures.

Designers who try to appear more ‘accessible’ to a non-luxury market of consumers miss the point. If I wanted to wear scrubs as a fashion statement, my first port of call wouldn’t be Prada SS 2011. My sister, who is a nurse, didn’t recognise the ‘minimal baroque’ intended by Miuccia Prada. She called it “nurse chic” but urged Miuccia to “smear some blood over it to make it more realistic”.

Image courtesy of Osman Yousefzada

Nurses were never the intended demographic – their salaries are far behind the models on Prada’s runway. If high fashion wants to be truly accessible, then it must be affordable, accessible and authentic. A good start would be to bring working-class creatives into more design teams, reflecting a sense of the ‘real’ world rather better than so many modern-day design teams that seem to live in ivory towers divorced from real-life economics.

Research suggests only 16 per cent of people in creative jobs in the UK are from working class backgrounds. As many as 80 per cent of journalists are from relatively privileged backgrounds. If these figures are even remotely accurate, then our knowledge and understanding of fashion are being communicated to us by a singularly privileged group.

Image courtesy of Osman Yousefzada

These figures become less shocking when we consider the frameworks that operate within the fashion industry. Top of the list are unpaid internships. To gain access to the exclusive world of fashion without industry connections or family connections, internships offer hope of a foot in the door. However, the intensive (and occasionally exploitative) nature of many internships, coupled with a lack of pay, means they’re taken up by those privileged enough to forgo a steady salary. The fashion industry claims they are gaining useful insight and experience. But who is really benefiting from this free labour?

That’s why it’s so important to celebrate and acknowledge the working-class talents who are shaking things up from the inside. I see some signs of hope. To take one example: Osman Yousefzada, a visual artist, designer, writer, and social activist from Birmingham, in the Midlands. His memoir, The Go Between, is a critically acclaimed account of growing up in 1980s Birmingham in a closed Pakistani migrant community. Drawing inspiration from his own life experiences, Yousefzada launched his label, Osman, in 2008 in which he explores the many facets of his identity through design.

Yousefzada’s most recent collection, for Autumn 2022, has a cast comprised of brown queer activists such as Parveen Narowalia, Ryan Lanji, Deepanshu Sharma, Anita Chibba and Sheerah Ravindren. With its fringing, voluminous ruffles and fuchsia feathers, this collection sidesteps the conventional glamour of high fashion.

Image courtesy of Osman Yousefzada

Instead, his pieces are interwoven with the narratives of Yousefzada, his cast, as well as the artisanal makers, weavers and embroiderers in India who produced many of the garments in partnership with the designer. Yousefzada’s efforts to give space to new narratives are not limited to his designs. His first short film, Her Dreams Are Bigger, aired in 2018 and shines light on the dark side of fashion by documenting the realities of fast-fashion garment workers in Bangladesh.

It’s tough out there. But designers such as Yousefzada are setting new standards for innovation and authenticity. It’s almost enough to make me feel confident.