Excessive digital retouching is one of those recurring topics beloved of Planet Fashion’s peanut galleries and the media that feed them, rather like underweight models, catwalk racism, and the return of classic beauty, the muse, and bias cuts. The debate could be quashed by pointing out that fashion and advertising photography is really a form of commercial art, another way of delivering the ink to the paper to create the desired image, rather than photography in the purist sense of capturing an instant of reality through the camera lens. But where is the fun in that?

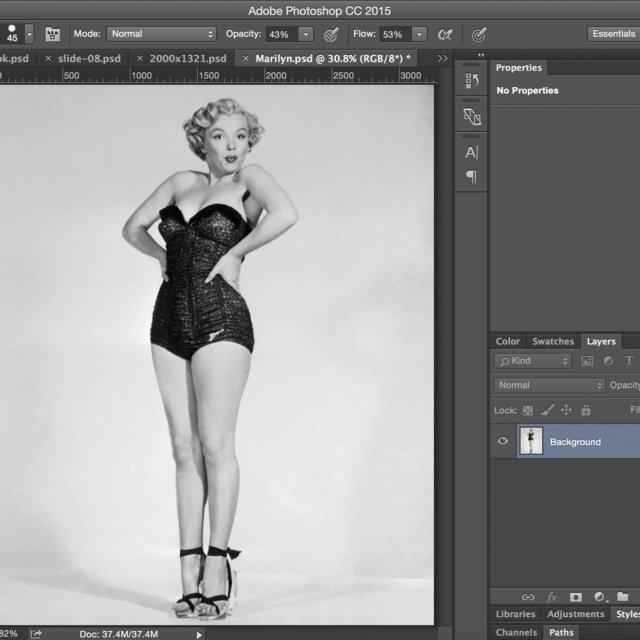

Retouching can be a necessary evil, particularly in the case of new fashion photographers who have everything going for them except photographic talent, or celebs who might in times gone past have been smothered at birth or sold to a passing freak show. Even Instagram offers users basic retouching tools. As photographer Gavin Bond said, “We are living in a society driven by social media where it’s expected that people look a certain way. Now people are even retouching their selfies on Instagram. That’s crazy! When I first started having my images retouched, it involved a scalpel and a fine paintbrush. Today, there is too much use of the term ‘fix in post.’”

Harri Peccinotti, who trained as a commercial draftsman and graphic artist before adding photography to his skills, said of fashion and advertising shoots, “Retouching is obviously a necessary part of post-production, but sometimes you feel, on a shoot, that everyone, from the photographer to the stylist, is worrying a bit too much about how the retouchers will process the image.” “So, the chimpanzees have taken over the monkey house, eh?” I reply. Peccinotti’s eyes twinkle. “I wouldn’t put it quite like that, but some of them do seem to exert an excessive influence.”

Back in the day, when most of us still had typewriters on our desks and Tippex on our fingers, managing editors and publishers would rant and rail about excessive photo lab charges. As one retoucher with a nicotine-stained quiff and a brown lab coat pocket full of scalpels and fine paint brushes told me in a Michael Caine accent, “You’re not paying for me to make this photo look better, son. You’re paying for the decades it took me to learn how!”

It is tempting to remark that the difference between the retouchers of the last century and nowadays is that they aimed to make images look better whilst their heirs seem bent on making them look the same. Photographic manipulation is easier these days thanks to an arsenal of user-friendly software, and it takes less time to train a retoucher, but the labs are still charging us through the nose, often in cahoots with the photographers or their studio managers. Of course, they are not all vampires and necrophiliacs, but one can sometimes lose sight of this comforting reality.

A couple of years ago, one top fashion photographer’s studio manager told us we had to use his lab of choice. The lab demanded €175 per image in advance for ‘retouching’ that amounted to little more than redlining the contrast and denuding the images of the documentary-style edge that gave them that authentic feel. We replied that we would not be publishing the series. Spaghetti western face-off moment. They blinked first, toning down the contrast and the price to just €40 an image; quite a climb-down from the starting price.

Peter Lindbergh, known for the striking authenticity of his images and his aversion to excessive retouching, is clear on the topic. “I have listened to so many stupid discussions about retouching. If you do heavy retouching, like altering proportions, you are taking the truth out of your images. Truth means accepting things the way they are and this is quite important. To accept imperfection makes you a human being. There cannot be beauty without truth.”

Leni Riefenstahl, whose aesthetic haunts the images of many fashion photographers, saw her quest for beauty differently, telling me in 2002, “I have an aversion to stark reality, to real life. For example, if, in a shot, there is wastepaper or an empty bottle, something ugly, that would bother me. I do not want to see it. I can’t. Impossible! I don’t even register it. That kind of realism, I do not like.”

There is no rubbish or litter in the streets through which the massed ranks of Nazi Stormtroopers and workers march in Riefenstahl’s Triumph of the Will. Her assistants saw to that. Her later documentaries are similarly clean. Her African tribespeople are not roasting rats over smoldering car tires. Her underwater films do not show the empty bottles, used condoms, and floating turds we mere mortals have to negotiate when diving on reefs.

Not that this diminishes Riefenstahl’s talent and art. Photography is seldom about what the photographer sees through the lens but what the photographer wants the audience to see. Lee Miller was sometimes said to have rearranged corpses in the Dachau concentration camp after its liberation in 1945 to improve the composition and impact of her shots, subsequently published in Vogue magazine. The paparazzo who got the money shot of the dying Princess Diana was widely suspected of climbing into the car to move her head for a better angle.

Anyone who believes photography to be a completely reliable record of reality is deluded because it never was. Photographic manipulation is as old as photography, as the New York Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Faking It exhibition reminded us in 2013. Documentary photography offers us a version of reality, while fashion and advertising photography offer us dreams. Or not, depending on our values and aspirations.