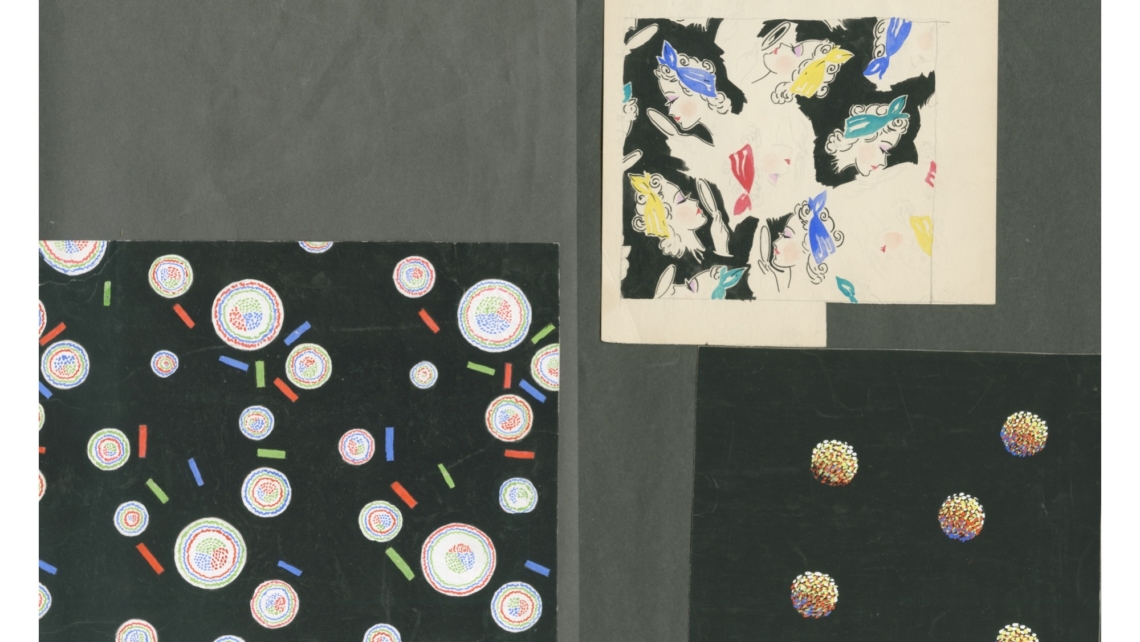

Writing about artist Michel Dubost in the preface to a 1930 table book entitled 28 Compositions for Silk Weaves by Michel Dubost, the French author Colette waxed lyrical about “he who weaves the sun, the moon, and the rain’s blue bands”. The tribute sounds even better in the original French: “celui qui tisse le soleil, la lune, et les rayons bleus de la pluie”.

Dubost had endured the horrors of trench warfare, rendering the beauty and otherworldliness of some of the pieces comprising the recently discovered hoard of his designs and samples that prompted this essay all the more moving. Dubost was so traumatized by what he experienced on the Western Front that he was demobilized and sent home in 1917.

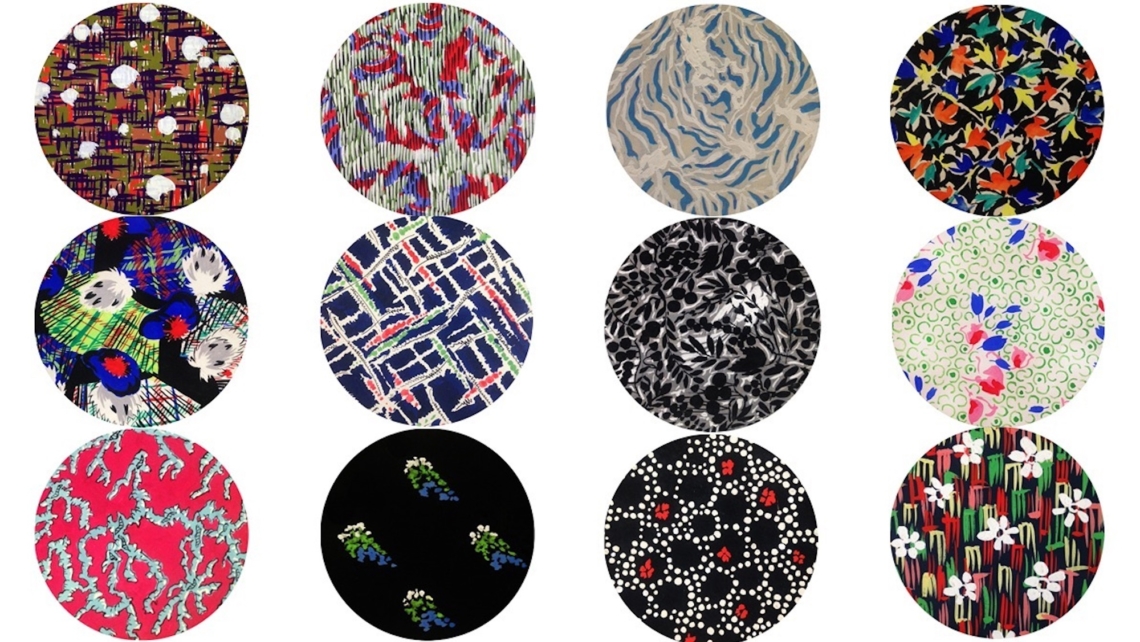

Born in 1879, Dubost died in Grasse in 1952. Over sixty years later, when some books from his private library were found in an old storage facility and publicly auctioned, the auctioneers nearly threw away a folder containing over a hundred original designs and a quantity of photographs, including the only three images of Michel Dubost known to survive.

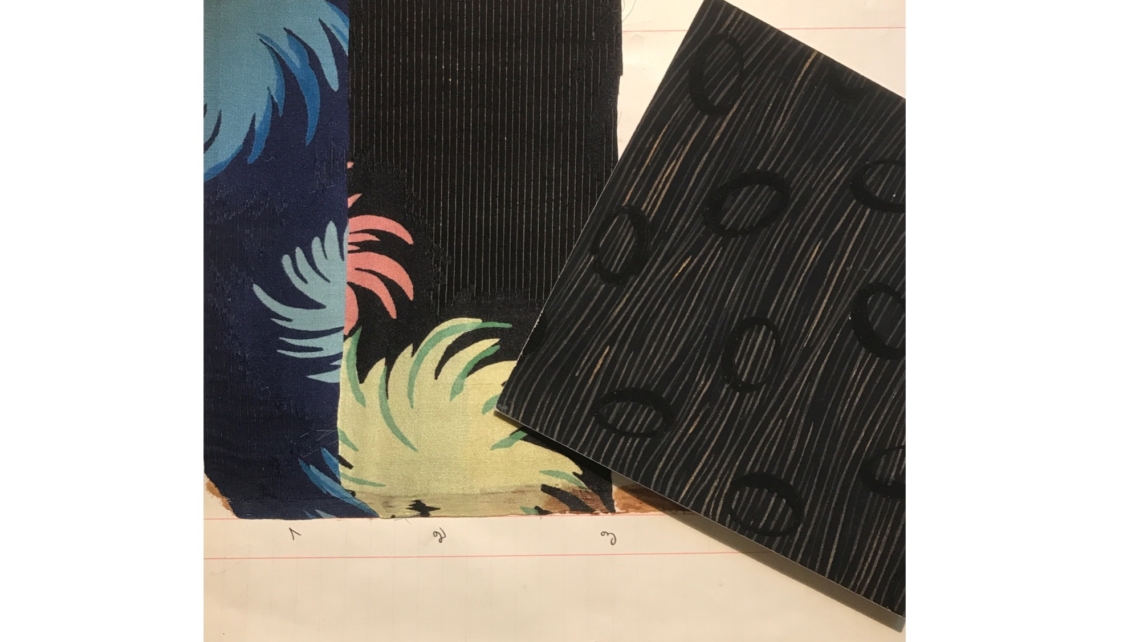

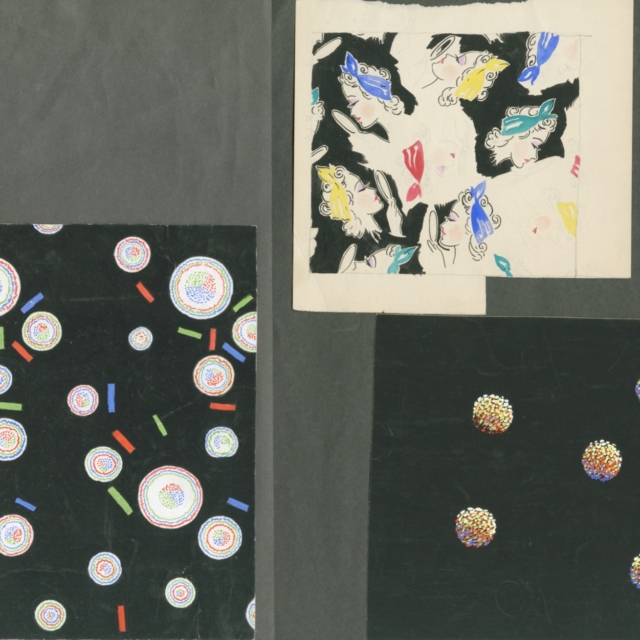

The folder contained a few samples of silk weaves, including a couple of extremely light pieces interwoven with very fine gold threads, one of which incorporates yellow, red, and white gold. Amongst the designs executed in paint and ink on paper is a gold and black motif closely resembling the fragment of black silk with gold thread.

Some curators and students of fashion history believe Colette’s dreamy passage to be a tribute to Ducharne rather than Dubost but they may not have seen the original book, which unequivocally gave Michel Dubost top billing and which, moreover, was commissioned by François Ducharne as a tribute to his collaborator and friend.

The organizers of the 1975 retrospective Les Années Folles de la Soie at the Musée Historique des Tissues in Lyon gave Ducharne’s name top billing on the catalogue’s title page, immediately followed by Colette’s words. Dubost is credited further down the page. Had he still been around in 1975, Ducharne would surely have abhorred this revisionism.

However, the exhibition was supported by the Lyon Chamber of Commerce and Industry and the late François Ducharne was, of course, one of their own. Michel Dubost had died over twenty years earlier at his home in Grasse in 1952 and, as any business person will tell you if you stand still long enough, artists are ten a penny and would starve but for business people.