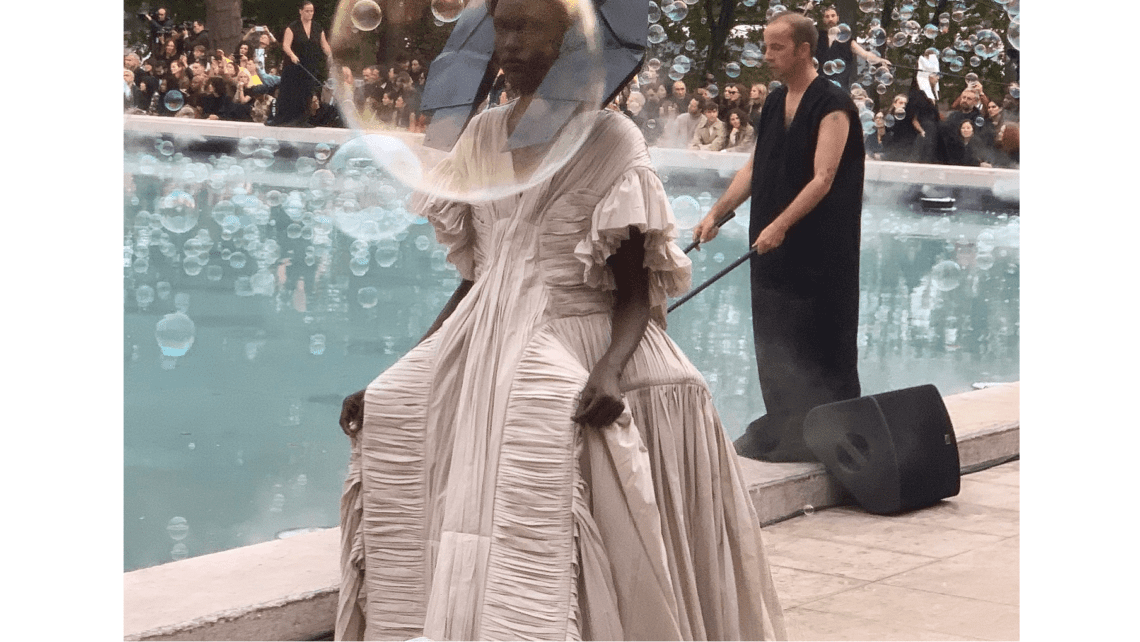

White was everywhere on the Spring 2020 Paris runways. It opened the shows of Valentino, Off-White, and Alexander McQueen. It closed Miu Miu, Louis Vuitton, and Dries Van Noten’s arresting collaboration with Christian Lacroix. Even Kei Ninomiya, the Japanese designer behind Noir, turned to white for the primary palette of his collection, an otherworldly feat of construction he titled “Beginning.”

White is often read as a new beginning—a blank slate. It also suggests going back to the beginning—back to basics, a theme Pierpaolo Piccoli, Miuccia Prada, and Loewe’s Jonathan Anderson touched on in their collections, all of which were at times lavish, at times stripped down to immaculate takes on the essentials. Were fashion’s biggest players trying to tell us something? Headlines during PFW warned of a global recession and called for action against climate change. To be sure, sustainability and going carbon neutral, as Kering has pledged to do, were hot topics this season, with numerous companies and designers shouting their eco-friendly accomplishments through press releases—some earnestly, some not so much. But I don’t think the proliferation of white wares was about that. It seemed to be more about creative purity and unlikely optimism. Or maybe designers just know that people like to wear white in summer. Either way, it felt like the needle moved in Paris—and there was something uplifting about that.