While she’s excited for the shoot, Lucy also shares how she often feels nervous about using models – all of whom have become good friends since working closely with them at FFORA – in their promo. Many such new talents, such as Jourdie Godley and Bri Scalesse, have been able to launch modelling careers after their shoots were picked up by the likes of Teen Vogue and High Snobiety.

“We feel such responsibility as well, knowing that we are saying something and putting people we have really close relationships out there.” Negative comments and trolls are inevitable, and is something Lucy tries to prepare her models, many of whom have no formal media training, for, as well as possible. But it’s also one of the designer’s favourite parts of the job. “We just have this pride that we are able to make connections and support the people we love, it’s been phenomenal.”

Jourdie, who often takes centre stage in their shoots, explains that FFORA is so much more than just an accessories label. “FFORA has brought me closer to my own community in ways that I would never have imagined before. Through FFFORA I have also met amazing photographers, stylists and friends that I will continue to work with from now on.”

Providing a platform for the disabled community in this way, while not intentionally planned, is an idea at the core of the company. In fact, Lucy exclaims, even the brand name FFORA is Latin for forum; a platform for speaking out (and not Fashion For All, as she explains has previously been erroneously published).

Within the fashion industry, there’s always a fear that a brand offering representation to a minority group might be treated as a short-lived curiosity. Lucy is conscious that she doesn’t want to be seen as a saviour for the disabled. I push for her thoughts on the subject; what are her recommendations for building a brand that is sincere about lifting the disabled community and not treating it as a novelty?

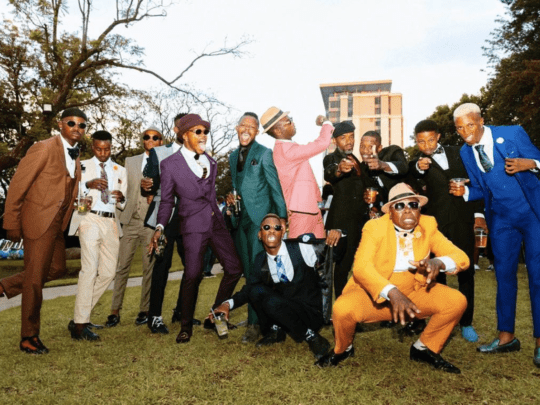

Photo: FFORA

“If people are going to be sincere, they need to touch every aspect of the company. They need to train everyone from their leaders, all the way down to the retail staff in their stores.” She dislikes inclusivity departments, she adds. “You can’t just have one group passionate about it and desperately trying to educate their colleagues.”

Her thoughts aren’t just her own but are also shared by those in the community whom she interacts with daily. “People with disabilities would love to have an accredited board to vet this sort of thing; to create a standard brands have to pass.” Without such, Lucy fears companies use the inclusion of those with disabilities as purely a PR stunt.

As a seated model and brand consultant himself, Jourdie is used to fighting for better representation within the industry and agrees with Lucy. “I honestly would like to see more people with disabilities in the industry in many capacities. To see seated models participating in runway shows and ad campaigns for major brands in an authentic way. By authentic I mean having the model actively participate without their disability being highlighted and them being treated just like every other model,” he explains.

Lucy accredits the slow improvements to a lack of education. “There are so many simple things that transform life for a person with a disability.” Mentioning an incident where a friend was unable to purchase anything in a store because all they used were small buttons, Lucy explains that oftentimes cost is what stops brands from being inclusive. “As a designer, knowing how these products are seen and produced, everyone knows it’s cheaper to do small buttons.” This issue could have been resolved with bigger buttons more spaced out, in order to cut even on costs and allow more people to use the product. “There are so many simple changes and it’s so frustrating.”

Brands who claim to be inclusive but aren’t give Lucy another reason to be sceptical of the industry. “I really think it shows when you’ve done your research – did you even have someone who has a disability in the room when you made the decision?” Similarly, Jourdie argues, “True representation starts from within, not on Instagram. By having people with disabilities out in the Industry people’s perceptions of us will hopefully change for the better.”